by Olivier Thévenon, Head of the Unit, Chris Clarke, Economist, and Gráinne Dirwan, Policy Analyst - all at Children’s Well-being Unit, OECD Centre for Well-Being, Inclusion, Sustainability and Equal Opportunity

Childhood is a critical period in which individuals develop many of the skills and abilities needed to thrive later in life. Promoting child well-being is not only an important end in itself, but is also essential for safeguarding the prosperity and sustainability of future generations. As the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates existing challenges—and introduces new ones—for children’s material, physical, socio-emotional and cognitive development, improving child well-being should be a focal point of the recovery agenda.

To design effective child well-being policies, policy-makers need comprehensive and timely data that capture what is going on in children’s lives. Our new report, Measuring What Matters for Child Well-being and Policies, aims to move the child data agenda forward by laying the groundwork for better statistical infrastructures that will ultimately inform policy development. We identify key data gaps and outline a new aspirational measurement framework, pinpointing the aspects of children’s lives that should be assessed to monitor their well-being. Our findings build on insights from research literature, as well as the OECD’s previous work on child well-being including the 2009 Doing Better for Children report; the How’s Life for Children chapter in the 2015 edition of our How’s Life? Report; our OECD Child Well-being Data Portal; and the wider OECD Well-being Framework.

What are our main findings?

Our research shows that, although the availability of cross-national child data has improved considerably in recent years, comparable data is still lacking and limited in scope. Some areas of children’s lives are measured better than others. For example, there is little data on children’s “social capital”, meaning their perceptions of their social and cultural identities, participation in group activities and knowledge of global and societal issues. We also found that existing data often fail to represent certain age groups: there is limited information on the well-being of children under school age, especially in comparison to adolescents.

Unequal data representation can be observed across different population groups. Children in the most vulnerable or marginalised positions—including those who are disabled, in homeless families and victims of domestic violence—are often missing or not easily identifiable in existing datasets. In addition, children’s views and perspectives are not always well heard. There tends to be limited information on their own attitudes towards many aspects of their lives, restricting the extent to which existing policies are able to address their main concerns.

Finally, a common thread that we have identified throughout our research is that existing cross-national child data are not reflective of the interconnected nature of child well-being. Datasets frequently fail to link the different dimensions of children’s lives and therefore do not account for how outcomes in a given area, such as physical health, may have an effect on others like socio-emotional well-being.

How can we do better?

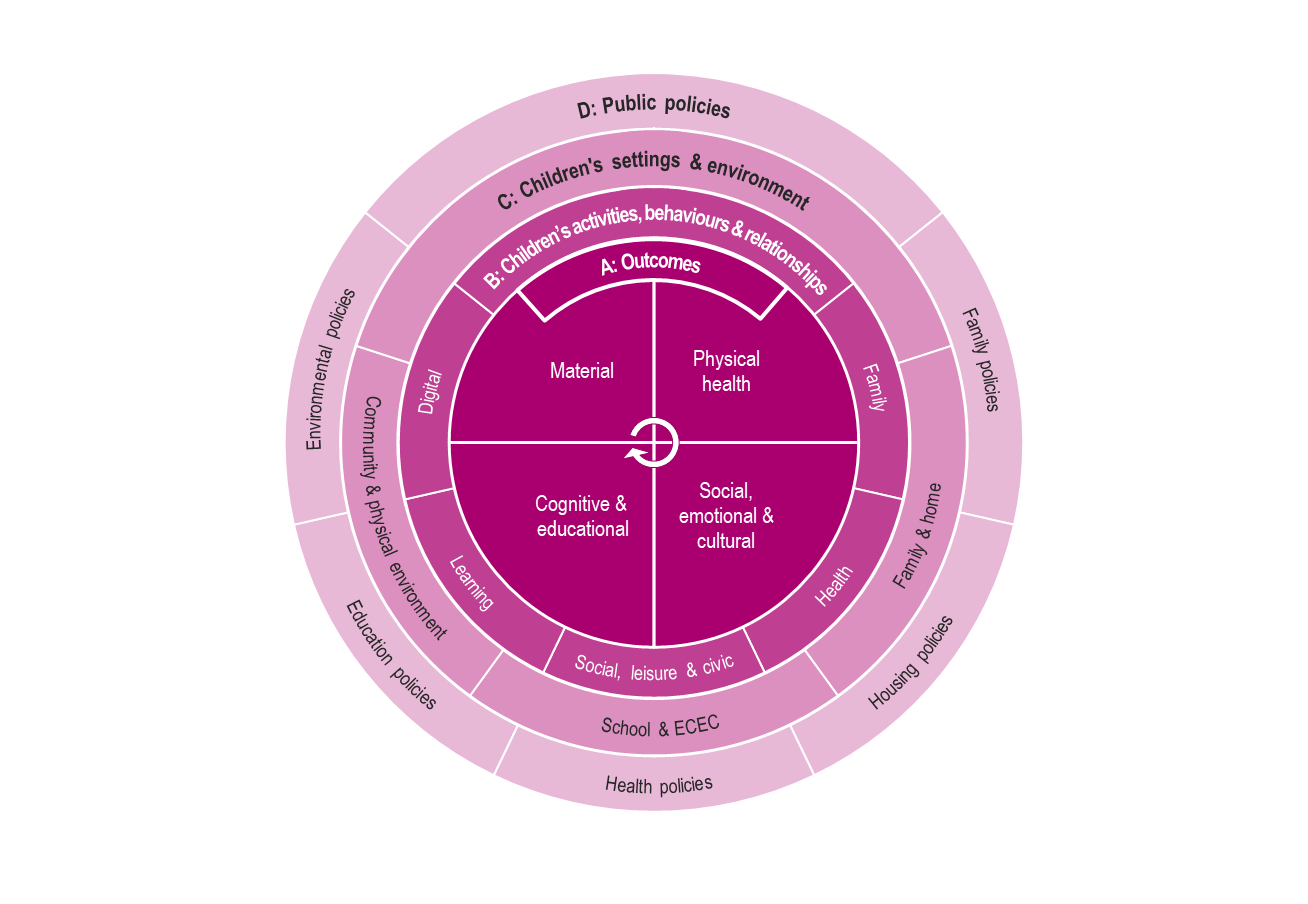

Child well-being is multidimensional. If we undertake a “siloed” approach to producing child data, we will not have a solid grasp of what is really going on in their lives. Our new measurement framework highlights these multiple interactions, between the different areas of children’s lives and within the larger environment they grow up in. At the core of the framework’s multi-layered structure are four main dimensions for monitoring children’s well-being: material living standards; physical health; social and emotional outcomes; and learning and educational achievements. Subsequent layers reflect the essential role of children’s families, schools, neighbourhoods and larger communities in shaping their well-being by providing support, security, resources and opportunities. The framework also emphasises the importance of developing age-sensitive indicators that recognise the changing nature of children’s needs as they grow, as well as the importance of incorporating children’s views and perspectives in measurement.

An aspirational measurement framework reflecting the interconnected nature of child well-being

In order to further improve child data at both national and cross-national levels—and ultimately develop better child well-being policies—we need co-ordinated action and long-term commitment from governments, international organisations and the wider international community. We need to increase the regularity and timeliness of data collection, as well as the reach of techniques for combining data from multiple sources to build robust datasets. In particular, it is essential to strengthen the capacity to collect data on the well-being of children in vulnerable positions. Our hope is that the OECD’s new measurement framework will serve as a roadmap to improve the use of existing child data and motivate improvements in child well-being policies.

NOTE: This article was first published on The OECD Forum Network, the Organisation’s online engagement platform, and you can read the original article here.