By Charlotte Bilo and Sólrún Engilbertsdóttir

We have seven years remaining until the end of the 2030 Agenda – this means we are more than halfway through the period of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which was launched in 2015. The global landscape has changed drastically since the launch of the SDGs - we have witnessed unprecedented crises, the climate emergency, the COVID-19 pandemic, increased conflicts, heightened food prices, and inflation, affecting primarily the most vulnerable, including children. Save the Children and UNICEF projected that the pandemic pushed an additional 150 million children into multidimensional poverty. Approximately 1.2 billion children were multidimensionally deprived at the height of the pandemic. The SDG Agenda to accelerate efforts to end extreme child poverty and halve multidimensional child poverty has never been more pressing.

HOW COMMITTED ARE COUNTRIES TO THE SDGS OF ENDING CHILD POVERTY?

But is there a way to assess countries' commitment to the SDGs, including efforts to end child poverty? One way to determine this is to survey the data and narratives governments provide in their Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs). Each year a select number of countries present their VNRs to the United Nations High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF). The VNRs are the primary mechanism for tracking progress on the SDGs at the national level and reporting on it at the global level. Since 2019, the Global Coalition to End Child Poverty has reviewed the VNRs from a child poverty perspective, looking at how countries address and discuss their efforts to end child poverty through measurement and policies. And this is what we are seeing:

Out of the 262 VNRs submitted by 179 countries since 2017[1], most countries report on overall monetary poverty. However, many still don’t provide estimates on monetary child poverty (30 per cent), and only a minority (13 per cent) provide multi-dimensional child poverty estimates. We need a significant push for countries to measure both monetary and multidimensional child poverty.

On the other hand, there are significant variations between regions; more countries in Latin America and the Caribbean and Eastern Europe and Central Asia report on monetary child poverty. The most significant gaps can be observed in the Middle East and North Africa, and South Asia regions. As for multidimensional child poverty, the Eastern and Southern Africa, South Asia, and West and Central Africa regions have the highest proportion of countries reporting on multidimensional child poverty. High-income countries need to perform better; only one of the VNRs submitted by other high-income countries reported multidimensional child poverty rates.

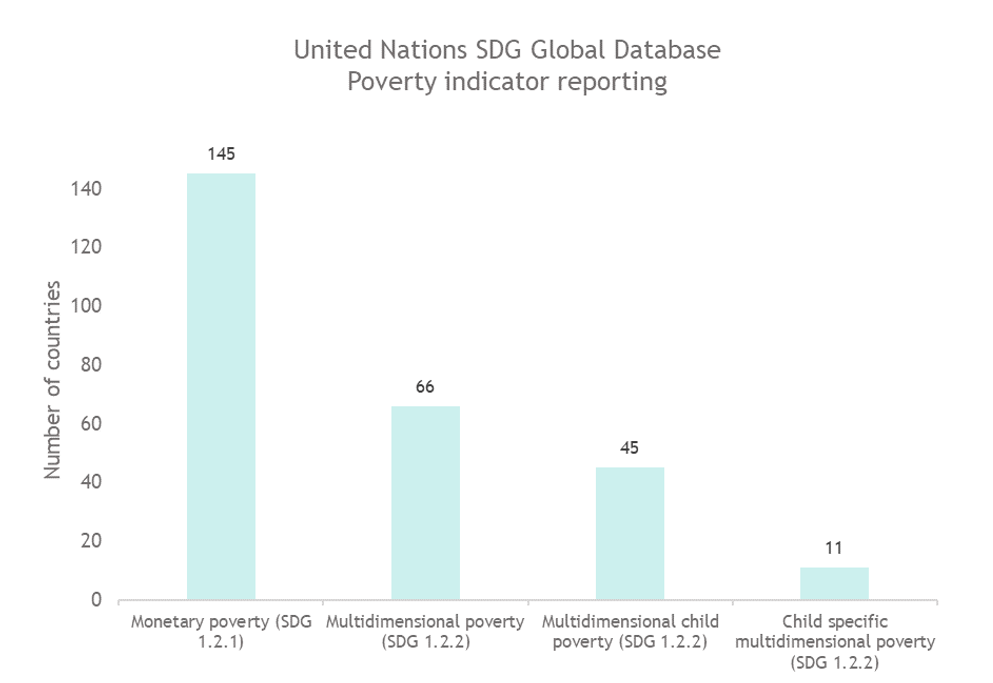

The VNRs are the most official global tool for countries to showcase their progress in achieving the SDGs. However, there are various other databases where countries can provide their SDG-related data to measure improvements, such as the SDG Global Database. According to the SDG Database, we see a slightly more optimistic picture - with 45 countries having reported on multidimensional child poverty disaggregated by age. Still, only 11 countries reported on child-specific multidimensional poverty.[2]

FIGHTING CHILD POVERTY REQUIRES COMPREHENSIVE POLICIES, PROGRAMMES, AND BUDGETS

Yet, measurement alone will not end child poverty. Once targets for reducing and eradicating child poverty have been set, these must be followed through with strategies, policies, programmes, and budgets to support families and children living in poverty. In this sense, it is encouraging to see that 32 out of the 43 VNR countries submitted in 2022 mentioned their efforts to tackle child poverty through various policy and sector-specific actions.

Efforts in building and expanding child-sensitive social protection systems were among the most common country-level responses to child poverty, outlined in the VNRs. For example, Argentina mentioned their `Prestación Alimentar´ which aims to supplement household income to purchase food, targeted at households with children up to 14 years of age, pregnant women and people with disabilities, and mothers with seven children or more. In May 2021, the benefit amount was increased for households with three children or more.

Several countries reported on the policies and programmes they have implemented to strengthen access to education, health, and other vital social services to address poverty. One example is Jordan, which increased efforts to build and better equip kindergartens and to deliver school nutrition programmes in poverty pockets and refugee areas, which increased enrolment in kindergartens.

Including child poverty as a critical priority in national development frameworks, such as in a national development plan or a poverty reduction strategy, demonstrates high-level political commitment, laying the groundwork for increased and more coordinated actions to combat child poverty, as well as funding to ensure implementation. Greece demonstrated this high-level commitment through the introduction of a strategy for social inclusion and the fight against poverty and the first National Action Plan for the Protection of Children’s Rights (2021), which include aims to reduce child poverty and guarantee that every child has access to free health services, education, childcare, housing, and adequate food.

WAY FORWARD

While the low number of countries reporting on monetary child poverty is worrying, the solution is not complicated: Most countries report overall monetary poverty rates in their VNRs, meaning that they already collect the necessary data to calculate poverty rates for the overall population, which is an important starting point to make the calculations for children. This practical UNICEF guide explains the different approaches to measuring monetary child poverty.

The low number of countries reporting multidimensional child poverty is one of the critical gaps identified in the 2022 VNRs. It is important to unpack and analyse the different dimensions of multidimensional child poverty (e.g., early childhood care, education, healthcare, nutrition, housing, and living standards) to design effective policies. There are different approaches to measuring multidimensional child poverty, as the Coalition’s Guide A World Free from Child Poverty explains (see also these resource pages for more on MODA and MPI).

While more countries reported on their efforts to build and expand child-sensitive social protection systems, many countries did not yet mention placing children at the heart of their social protection efforts in their 2022 VNRs, indicating a severe gap in policy responses to shield children from the lifelong consequences of poverty.

Moreover, despite the increase in the number of countries that discussed child poverty-related policies and programmes in their VNRs, coordinated and comprehensive national plans to reduce child poverty were generally not reported on.

As for the SDG database, some countries probably collect the necessary child poverty data but do not report it in the SDG database.

These gaps call for urgent action from national governments and the international community.

LOOKING AHEAD TO THE 2023 VNRS

As of January 2023, 41 Members States have committed to submitting their VNRs in 2023, most of which will report for the second time on their SDG progress.

The Coalition expects to see the proportion of child poverty-related numbers and narrative improve and calls upon countries to:

Report on SDG 1 child poverty indicators to establish a baseline, monitor progress, and guide policies.

Develop and implement a comprehensive national agenda to reach the SDG child poverty targets.

Support non-state stakeholders' participation, including impoverished individuals, in developing the VNR.

Share innovative national strategies to measure and address child poverty.

The Coalition, which encompasses a broad base of civil society, development practitioners, and researchers, stands ready to support countries in their VNR preparation process and to act as a platform to facilitate inter-country exchanges in this area.

—————————————————————————————————————————

Read the complete analysis and the summary here. Check this ‘traffic light’ overview dashboard of how countries have reported on child poverty in their VNRs and share the Global Coalition’s analysis among your networks.

For a compilation of tools that can be useful in preparing the 2023 VNRs, see also here.

[1] Some countries have submitted their VNR more than once.

[2] Unfortunately, the UN SDG Global Database does not include age-disaggregated figures for SDG indicator 1.2.1 on the proportion of the population living below the national poverty line, which calls for disaggregation by sex and age.

Charlotte Bilo is a Child Poverty and Social Protection Consultant, and Sólrún (Sola) Engilbertsdóttir is a Social Policy Specialist at the Child Poverty and Social Protection Unit at UNICEF.